There are two kinds of objectives encountered when renovating legacy manufacturing facilities: opportunity-based and risk-based.

- Projects that are primarily opportunity-driven seek to create a business advantage through facility transformation – usually through improvements in capacity, quality or efficiency. These are the fun projects; the ones most easily justified by return-on-investment, but also the projects that all too frequently never happen because they fall victim to the tyranny of the urgent.

- Projects that primarily mitigate risk are motivated by loss aversion. These projects are primarily driven by an unacceptable business risk associated with people, property or product. These are often the high-profile remediation efforts that jump to the fast track after an accident, loss, or regulatory observation.

Most renovations are not purely opportunistic, or risk driven. Project objectives typically include a combination of opportunity and risk drivers. Facility renovations are disruptive, so it makes sense to take care of as many issues as you can during construction. However, the objectives of the project, for many reasons, are not always universally understood by everyone on the team.

Without a shared understanding of desired project outcomes, priorities can be confused, owner stakeholders often send mixed signals, and suppliers end up disappointing their clients. A consensus of shared objectives is particularly important when developing a scope of work and is a critical component for decision-making throughout the entire project life cycle.

Project Objectives Identified

As part of Facility Focus, an industry-wide survey of the life sciences industry conducted in partnership with INTERPHEX, industry insiders – those in engineering and operations roles – were asked to rank the most frequent capital project objectives they encounter when renovating manufacturing space. They identified the following most common capital project objectives, listed in order of frequency:

- Opportunity-Based Objectives

- Increase process throughput

- Retrofit for new product or process

- Increase facility flexibility

- Risk-Based Objectives

- Improve product quality

- Achieve regulatory compliance

- Improve reliability

Note that none of the opportunity-based objectives is mutually exclusive with the risk-based objectives. In fact, it’s frequently more efficient to execute projects with multiple compatible objectives under the common overhead of a single project. To do so takes careful planning, and perhaps the willingness to invest in some front-end feasibility analysis and engineering studies to refine the scope. It is very common though. And when this multi-objective project is tied to a schedule and budget, it’s critical that the project priorities are well-understood.

A Problem of Perspective or Perception?

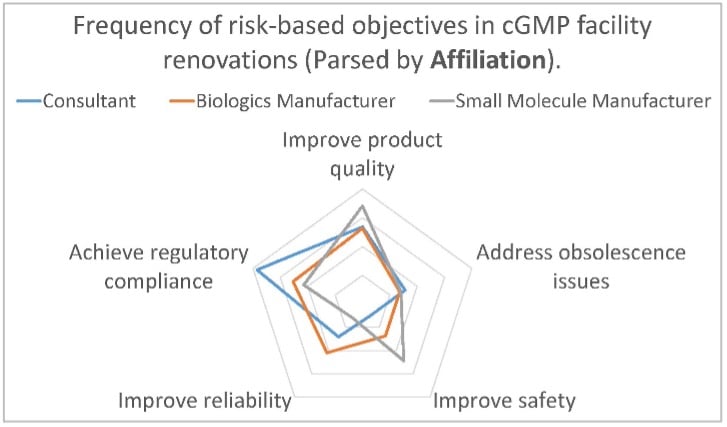

An interesting thing happened when we looked at the survey data broken down by the participant’s affiliation and job function. We were seeing a divergence in terms of the most common reported project objectives. For example, when we asked survey takers to rank the frequency of risk-based capital project objectives in cGMP facility renovations, we saw a significant divergence in the responses. The radar chart below illustrates the data parsed by the survey participant’s affiliation.

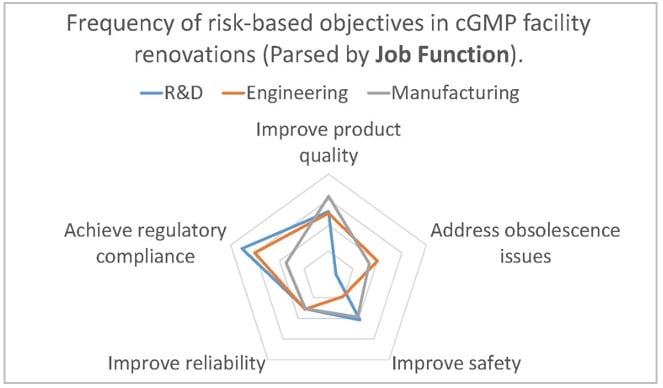

When the same data is parsed by the respondent’s job function, we saw a different frequency distribution.

Some of these deviations made sense when you considered the perspective of the participants. For example, it’s entirely plausible that participants from an API chemical manufacturing operation (small molecule), which typically involves processes with flammables and combustibles, would more frequently encounter projects in which safety improvement was an objective.

Likewise, it’s not surprising that those from an R&D background, where the central mission is to develop new products and processes, were less likely to encounter capital projects addressing obsolescence issues. However, other deviations were not as easy to explain.

Why would those working in engineering roles be less likely to encounter projects where safety improvement is a major objective? Why would those representing consultants be more likely to engage in projects where GMP compliance is the primary objective than those who are engaged in GMP manufacturing? In these cases, the divergence in response is most likely due to a difference in perspective.

Those in manufacturing roles are incentivized to see safety improvements as a key objective (it’s their safety we are assuring after all), while those who are supporting manufacturing in engineering roles are more likely to see safety as due diligence, rather than a key project goal. Likewise, those who work for manufacturers are

more likely to overlook project objectives related to GMP compliance because they aren’t used to thinking about facility design in that context (in their day-to-day experience they think of GMP requirements in terms of its demands on operations).

But those who design GMP facilities for a living are always thinking about the impact of GMP compliance on facility design, process segregation and product protection (hence the perception that achieving GMP compliance is the foremost objective for these kinds of projects). I’m not saying that the survey reflects a cohort’s conscious choice to pursue different objectives, though stakeholders can and sometimes do advance a personal agenda. What I am saying is that we may be seeing a difference in perception. Our personal perspective – the context of our job responsibilities and relationships – can influence the way that we perceive and prioritize project objectives.

Leveraging Diversity While Aligning Priorities

Fielding a project team with diverse perspectives is good business practice, precisely because of the aforementioned difference in perspectives. This diversity ensures that all the needs of the organization are taken into account when project objectives are first established and helps to identify unintended consequences of choices made throughout the project.

However, the diverse roles and affiliations of project stakeholders also make it harder to establish a shared understanding of primary and secondary objectives, and to maintain these priorities throughout the life of the project.

This is where leadership is required from the project manager. Project managers should be the strongest champions of the project objectives. It is the project manager’s job to ensure that every aspect of the effort – from design to delivery – serves the desired outcome. They are responsible for casting the vision for the project and aligning the team’s efforts in a common direction so that everyone stays on mission.

This leadership starts with a clear articulation of all objectives and priorities, including schedule and budget, from the beginning of the project. Project objectives should be clearly stated in the project plan, in presentations to management, in requests for proposal from suppliers, and most importantly in the kick off meeting with the project stakeholders. These objectives should be revisited periodically throughout the project, particularly during periods when key design decisions are made.

When difficult decisions need to be made that balance competing priorities, this is the project manager’s compass for determining the right path forward. It’s time to remind the team of their shared vision and get everyone pulling in the same direction. Keeping the project team in sync with these priorities will go a long way toward assuring the success of the effort – as defined by the achievement of all project objectives.

The Facility Focus survey provides insight into the minds of industry insiders – those who have their share of war stories from experience with cGMP projects in legacy facilities.